Foreword: The Echo of the Gilded Age in Modern Fantasy Narratives

In recent years, two high-profile role-playing games have, despite their distinct core narratives and mechanics, drawn inspiration from the same captivating historical period. These are Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 (hereafter E33), slated for a 2025 release from Sandfall Interactive, and Lies of P (hereafter LoP), released in 2023 by Round8 Studio and Neowiz. E33 is an innovative turn-based RPG with real-time elements, focusing on a desperate expedition to break a yearly curse that erases people of a specific age. In contrast, LoP is a Souls-like action RPG that offers a dark retelling of the classic Pinocchio fairytale, set in a city ravaged by a puppet rebellion.

The common wellspring of inspiration for both titles is the historical period in France known as “La Belle Époque” (The Beautiful Era, approx. 1871-1914). This era serves as more than just a backdrop; it is a key driver of their aesthetic, atmosphere, and even thematic depth. The Belle Époque’s inherent duality—of progress and anxiety, beauty and decay—provides fertile ground for imaginative storytelling. E33 explicitly states it explores a “fantasy world inspired by Belle Époque France,” while LoP’s art director, Changkyu Noh, confirmed the choice was made to “encapsulate a city’s transition from splendor to ruin.”

This analysis explores how these two games interpret, adapt, and showcase this unique historical period in their world-building, art style, narrative themes, and gameplay experience, examining both their commonalities and significant differences. An interesting phenomenon to note is the diverse backgrounds of the development teams: LoP was developed by the South Korean Round8 Studio, while E33 comes from the French native Sandfall Interactive. This cultural difference may bring distinct perspectives to their interpretations. For the Korean team, the Belle Époque might be seen more as an exotic aesthetic symbol, full of visual and thematic tension. For the French team, however, this period may carry deeper layers of national cultural memory, allowing for a more nuanced local sentiment in how they pay homage to, critique, or reinvent this piece of their history. This difference in developer perspective adds another fascinating layer to understanding how each game utilizes the same historical canvas.

The Belle Époque: A Canvas of Beauty, Innovation, and Latent Tension

The Belle Époque generally refers to the period in France, and indeed Europe, from the late 19th century until the outbreak of World War I (approx. 1871-1914). It was a time of relative peace, economic prosperity, and rapid technological and cultural advancement, suffused with a spirit of optimism. The arts, literature, and entertainment industries (such as cabaret shows and the birth of cinema) flourished as never before. The Art Nouveau movement became an emblem of the era with its flowing, organic lines and strong decorative motifs, while the later rise of Art Deco, with its geometric shapes and symmetry, was already taking root, heralding a new aesthetic shift.

The era’s fascination with new technology—electricity, automobiles, the dawn of aviation—drove immense social progress. However, beneath this optimistic facade lay deep-seated social anxieties, class conflicts, and the shadow of future conflict, most notably World War I. It is this duality of light and dark, prosperity and crisis, that makes it perfect source material for dark fantasy narratives. As the developers of LoP noted, the Belle Époque’s “inherent duality of romance and turmoil” provides an engaging foundation for the game’s setting.

The Belle Époque is so well-suited for dark fantasy because its external splendor and internal tension create powerful dramatic conflict. Rapid technological and social change can easily be interpreted as the catalyst for disasters born of unchecked progress or human hubris. Even the era’s prevailing art styles can be reinterpreted to evoke a sense of gloom or sorrow. On a deeper level, the Belle Époque is often viewed nostalgically as a lost golden age, but this nostalgia is always tinged with the knowledge of the catastrophe (WWI) that ended it. This quality of being “haunted” by a future calamity makes it a potent backdrop for exploring themes of transience, inevitable decay, or cyclical destruction. In E33, the annual “Paintress” curse brings a predictable doom, echoing the imagery of a beautiful world constantly on the verge of collapse. In LoP, the Belle Époque-style city of Krat is already in ruins, directly embodying the fall of a golden age. Thus, the historical position of the Belle Époque as “the last summer before the storm” provides both games with a ready-made, deeply melancholic, and fateful thematic foundation.

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 – A Living Painting of Fleeting Beauty and Impending Doom

The art direction of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 skillfully blends the visual elements of the Belle Époque into a fantasy world that is vibrant and full of life, yet constantly under threat. The game is described as having a “fantasy world inspired by Belle Époque France,” a claim profoundly reflected in its visual interpretation.

Artistically, E33 merges the organic lines and floral motifs of Art Nouveau with the emerging geometric sensibilities of Art Deco. This fusion not only showcases the era’s beauty but may also hint at a world constrained by a structured, almost fated, curse beneath its ornate surface. As one analysis noted, this “Art Nouveau/Art Deco duality symbolizes nature and technology.” The game’s French title, Clair Obscur (Chiaroscuro), itself an art term for the use of strong light-dark contrasts, forms the core of its visual identity. “Every scene… is in a precarious balance, constantly evolving between revealing light and enveloping darkness,” which directly echoes the game’s theme of “beautiful things under threat.”

Its world is presented with surreal and dreamlike qualities, described as “a living, malleable canvas, constantly being rewritten by the ‘Paintress,’” reminiscent of Surrealist art and the style of artist Moebius. Interestingly, developer Sandfall Interactive initially considered setting the game in a “steampunk Victorian London” but ultimately shifted to Belle Époque France to create a “more unique and visually striking world.” This change highlights the developers’ deliberate, strategic choice to harness the specific aesthetic and thematic resonance of the Belle Époque for their narrative.

The game’s narrative centers on a mysterious antagonist, the “Paintress.” She awakens each year “to paint a cursed number on her monolith, and everyone of that age turns to smoke and fades away.” This is a powerful metaphor for an absolute power that dictates life and death through art, twisting the act of creation into an act of destruction. The “Gommage” (erasure) phenomenon and the annually decreasing age limit create an intense sense of an impending apocalypse and a race against time, twisting the Belle Époque’s forward momentum into a morbid countdown. The concept of the expedition repeatedly failing and reforming, inspired in part by the French novel La Horde du Contrevent (The Horde of the Counterwind), reinforces themes of perseverance, sacrifice, and the struggle against an overwhelming fate.

E33’s “interactive turn-based combat” combines traditional JRPG mechanics with unique real-time actions like dodges, parries, and precisely timed attacks. Producer François Meurisse stated, “We wanted to have this reactive turn-based feeling, to blend the best of turn-based with the best of real-time.” Every button press in combat triggers a camera movement, making it feel “almost like an action game.” This active and responsive combat can be seen as a reflection of the expedition’s desperate, moment-to-moment struggle for survival against a relentless countdown. The demand for precision in offense and defense only heightens the high-stakes nature of battle.

E33’s interpretation of the Belle Époque transcends a mere aesthetic backdrop. It transforms the era itself into a living work of art that is being systematically defaced and erased by the “Paintress.” The game’s title, its central villain, its fluid world, and its emphasis on art styles all point to a core idea: this is a fight not just for survival, but for the preservation of beauty and reality itself against an ontologically destructive artistic force. “Erasure” is the act of being wiped from this grand canvas. The expedition’s mission is thus elevated to a battle to save the painting itself, to stop the world’s brilliance and essence from being painted out of existence. This raises the stakes from mere survival to a metaphysical struggle over reality and art.

Lies of P: Krat—A Monument to Ambition and Disaster Beneath a Belle Époque Veneer

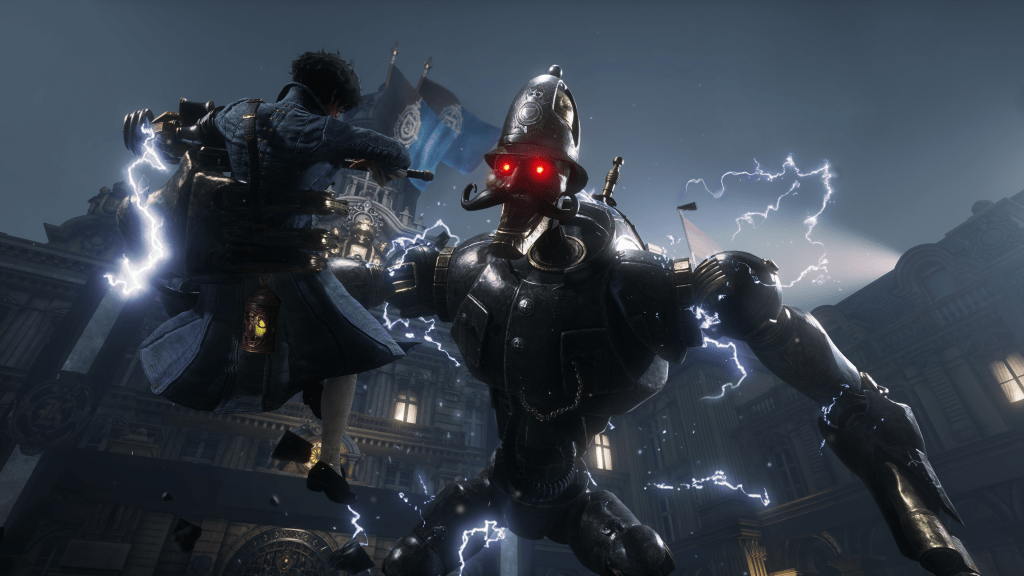

The architectural design of the city of Krat in Lies of P is explicitly modeled on the Belle Époque. Art Director Changkyu Noh mentioned, “To follow the architectural style of the Belle Époque, we referenced Ottoman, Neo-Baroque, and other unique styles.” The development team’s intention was to capture the opulence of the era while juxtaposing it with metallic structures and scenes of decay to create a “chilling, cold atmosphere” of post-apocalyptic desolation. This reflects the game’s narrative axis of a golden age collapsing into chaos, aiming to show “a city’s transition from splendor to ruin” and making the Belle Époque setting indispensable for visualizing this decay.

The game’s core narrative is a dark reimagining of The Adventures of Pinocchio. The protagonist, P, a puppet, embarks on a journey to become human after the “Puppet Frenzy”—a cataclysmic event where the city’s formerly subservient puppets turned on their creators. As a period of rapid technological advancement, the Belle Époque provides the perfect context for a story about advanced puppets and their potential dangers. “The Grand Covenant,” a set of laws compelling puppets to serve humans, represents the era’s belief in its ability to control its creations—a belief utterly shattered by the Frenzy.

“Lies” are a central theme of the game. P can choose to lie, and these choices affect the narrative and his progression toward becoming human. Art Director Changkyu Noh highlighted the Belle Époque’s “inherent duality of romance and turmoil,” suggesting the era’s superficial beauty could conceal underlying deceptions, much like P’s choices. The game borrows darker elements from the original Pinocchio story, including “black humor, cruelty, and fascinating characters,” which aligns perfectly with the grim atmosphere of the fallen city of Krat.

The challenging Souls-like combat system reflects the harsh, unforgiving nature of Krat after the Frenzy, where every encounter is a life-or-death struggle. The “Weapon Assemble” system allows players to create and adapt their tools, symbolizing the resourcefulness and scavenging needed to survive in a broken world—a kind of desperate innovation born from disaster. Meanwhile, the “P-Organ” system for character progression represents P’s internal transformation, evolving into something more, or different, through struggle and adaptation.

Lies of P uses the Belle Époque not just for its aesthetic of progress and decay, but as a symbolic stage to explore the tensions between the artificial (puppets, social facades) and the real (P’s quest for humanity, the truth behind the Frenzy). The era itself, a blend of true innovation and superficial spectacle, mirrors P’s internal struggles and external conflicts. Krat, a beautiful yet technologically advanced creation, brought about its own doom through its inherent fatal flaw. P’s “Lying” mechanic is key to his becoming human, suggesting that truth can perhaps be found through, or beyond, falsehood. Thus, the Belle Époque setting in Lies of P acts as a grand theater for a drama of the artificial versus the real. The ornate yet decaying architecture and the once-docile, now-murderous puppets all underscore this central theme. “Lying” is not just a game mechanic but a thematic exploration, asking what it means to be “real” in a world filled with beautiful and dangerous artificial creations.

Contrasting Visions: Two Games, One Era, Different Interpretations

The table below outlines how the two games interpret and utilize key aspects of the Belle Époque, allowing for a direct comparison of their approaches and highlighting their convergences and divergences.

| Feature | Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 | Lies of P |

| Primary Art Focus | Surrealism, Art Nouveau & Art Deco fusion, Chiaroscuro lighting. | Dark industrial realism, Neo-Baroque & Ottoman architecture, sense of decay. |

| Thematic Use of Era | Fleeting beauty, cyclical destruction, art as creation/destruction, fighting fate. | Technological hubris, societal collapse, falsehood vs. reality, the quest for humanity. |

| Depiction of Technology | Magical/Fantastical (The Paintress’s power), some engineering (Gustave). | Advanced puppets, Ergo as a power source, industrial machinery. |

| Overall Mood/Atmosphere | Melancholic, dreamlike, desperate, a “surreal, war-torn France.” | Grim, oppressive, decadent, a “dark and mad city.” |

| Nature of Antagonist | Abstract, artistic, elemental force (The Paintress). | A concrete product of ambition/society (rogue puppets, human corruption). |

| Protagonist’s Goal | Break the cycle of death and save the people. | Find their creator, become human, and uncover the truth. |

In art and architecture, while both draw from the Belle Époque, E33 leans into a more overtly artistic and fantastical interpretation, blending art styles into a world that feels like a fluid painting. LoP, however, roots its setting in a more concrete, albeit ruined, architectural realism, focusing on the grandeur of urban structures and their subsequent destruction. Its beauty is the wreckage of a failed utopia.

Thematically, E33’s core is a “fight against fate”—a pre-ordained, cyclical doom imposed by an external, god-like entity. The Belle Époque setting highlights the beauty that is being lost. LoP’s central theme is a “quest for humanity amidst deception”—an internal journey of self-discovery in a world where truth is elusive and society has collapsed from within. The setting here highlights the world’s artifice and broken promises.

In terms of technology and society, E33 is rife with fantasy elements like the Paintress, strange creatures called “Gestrals,” and a world shaped by magical art. Technology, such as the engineer Gustave, exists but is secondary to the magical threat. LoP is rooted in the consequences of its own creations: advanced puppet technology and the mysterious energy source, Ergo. Its societal collapse is a direct result of its own creations rebelling.

Atmospherically, E33, despite its dark premise, evokes a melancholic beauty and poetic tragedy, featuring a “breathtaking world” and “impeccable soundtrack.” Its “surreal, war-torn France” still contains elements of wonder. LoP presents a more consistently grim and oppressive atmosphere. Krat is a “dark and mad city” filled with danger, decay, and a pervasive sense of dread.

The developers’ origins also seem to subtly influence their interpretations. Sandfall Interactive, a French team, may be more focused on the artistic and philosophical legacy of their national heritage (Surrealism, existential struggles against fate). The Paintress as a villain has a uniquely artistic sensibility. In contrast, the Korean team at Round8 Studio may have viewed the Belle Époque more as a powerful aesthetic and thematic toolkit. They focused on its visually dramatic beauty and decay and its universal themes of ambition and collapse, which could be skillfully integrated into a globally appealing story like Pinocchio. This is not a judgment of quality but an observation of different potential focuses based on cultural background: cultural proximity (for Sandfall) might lead to a more nuanced exploration of the era’s artistic soul, while cultural distance (for Round8) might allow for a greater focus on its cross-culturally potent aesthetic power and its dramatic potential as a backdrop.

Conclusion: The Enduring Resonance of the Belle Époque in Interactive Narrative

In summary, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 transforms the Belle Époque into a vivid, surreal canvas for a story about cyclical destruction and artistic resistance, while Lies of P casts it as a grand, decaying stage for a drama about technological hubris, social collapse, and the search for a true self.

With its inherent contradictions of progress and anxiety, beauty and underlying darkness, the Belle Époque continues to provide a rich well of inspiration for contemporary game developers, especially in genres that rely on atmosphere and thematic depth. Its unique visual style offers a distinct aesthetic palette, while its historical position as a “Gilded Age” before a global catastrophe naturally imbues any narrative with dramatic irony and a sense of transience.

Ultimately, both games successfully leverage this shared historical foundation to create compelling and memorable worlds that effectively serve their unique narrative and gameplay goals. E33’s ambition is to create “a JRPG that is also an aesthetic and sensory experience, a tribute to art history.” Meanwhile, LoP successfully utilized the era’s “duality” to lay “an engaging foundation” for its setting. This is a testament to the versatility and enduring appeal of the Belle Époque as a creative wellspring.

Leave a comment